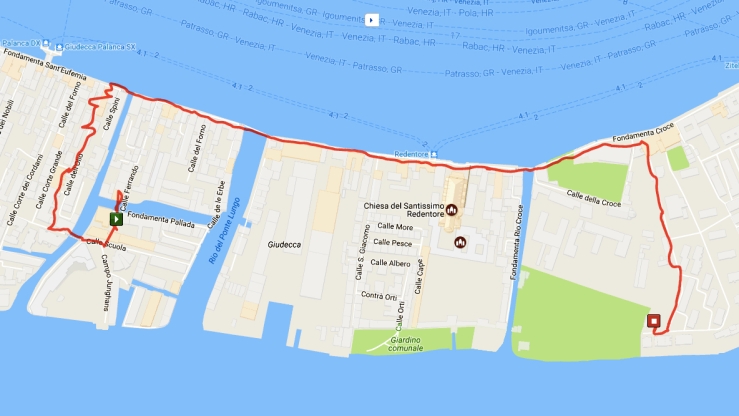

Of course there is a cat in the Garden of Eden. He is a young, brown and grey tabby, intelligent and sensual, quick and sociable. He heard us when we were looking at the garden from the other side of the Rio della Croce, talking and taking pictures. Up he sprang, lithe and confident, watching us with great interest as he walked along the red brick edge of the Eden Garden’s western border. He never looked once at the shimmering, muscular waters of the canal below him. But he did gaze at us, for quite a time.

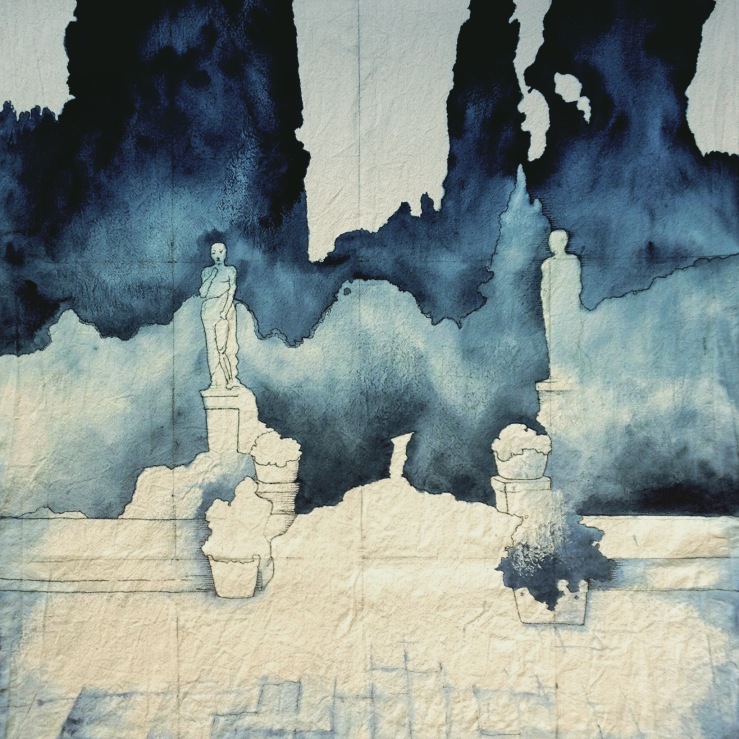

Perhaps 45 minutes later, we had made our way around to the garden’s south-eastern edge, where I made my first watercolour. As we talked, we heard a rustling in the leaves above the garden’s easterly red brick flank. To our happy surprise, it was our friend once more. He called out to us, and leapt nimbly down to our level, glancing off the banal grey mechanical boxes that have been installed against the wall here. Having been in Venice for a few days already, I had been reminded of the numerous homeless cats, not all of whom are friendly. This tabby, however, galloped over to us and seemed delighted to make physical contact.

The fact that he had just exited the garden so easily and swiftly, with a few quick bounds and turns, underscored the contrast between our gravity- and rule-bound selves and this little animal. What does he know? What does he see? What can he smell, remember, cherish about this garden? Surely he is what Donna Haraway would call a “situated knower” in relation to this space.

The Eden tabby shared the scents of the garden with us via his sensitive cheeks, whiskers, and ears, returning to rub our hands and clothes again and again. Although our sensory organs are not subtle enough to fully appreciate the tabby’s gifts of transfer and knowledge, this does not change the fact that he offered the garden to us in a way that his human counterparts have yet to do.

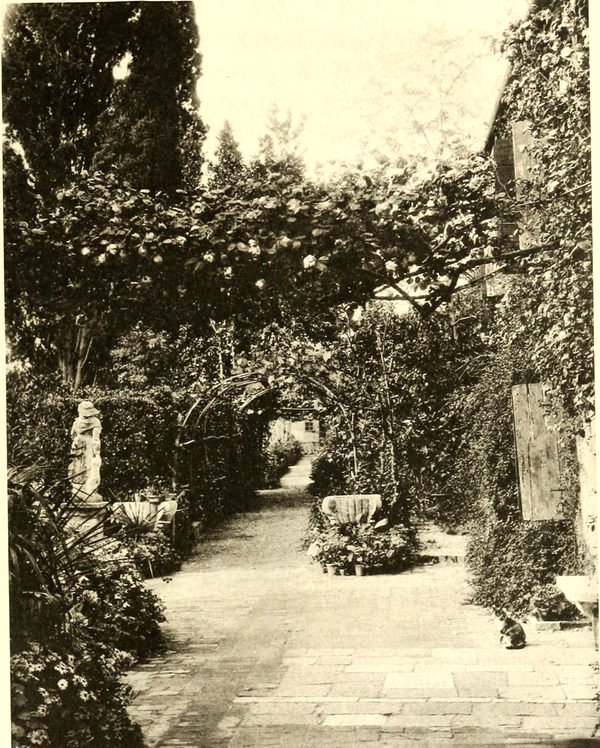

This tabby is not the first we know to have been familiar with this space. A photograph published in Frederick Eden’s book, A Garden in Venice, shows a self-possessed tabby sitting calmly on a flagstone courtyard. Although we do not know for absolute certain, it may be that Caroline Eden took this photograph.

A few days earlier, I had another animal companion as I sat and painted. Just as I began to make my image, a small white crane landed beside the watch tower that looks out over the garden and the lagoon. This tower is one of four such lookouts located at the corners of the former men’s prison that abuts the garden to the north. Judging from its appearance, it is a relic of the second world war. The higher walls that surround the former prison made for an excellent resting place for the crane, who sat – as I did – for almost an hour.

While at first they left the crane in peace, two large seagulls eventually could not tolerate its silent, almost motionless presence. As I was about to pack up, they flew in ever closer circles around the crane, shrieking at it, pressing it to leave.

And depart the crane did, swooping easily into the Eden garden, disappearing behind its wall in one, fluid movement. The seagulls did not follow.

We saw the crane once more, the following day, at the base of the western wall of the garden. She or he was looking for a meal in the seaweed exposed from the lower tides. The tabby appeared moments later.

These animal encounters remind me that while humans may be forbidden – mostly – from entering, there are many species for whom brick walls are not barriers but instead features of existence, things to be used, perhaps containing benefits, as protection maybe, or in service of movement as a conduit. As the crane cleaned its beautiful white feathers from its excellent vantage point, and as the Eden tabby’s velvety paws moved with precision and certainty along narrow bricks, the walls seemed to provide a sun-warmed stage, perhaps even a partner in daily life. We, for our part, were happy to provide the attentive audience to these performances of animal-urban relations.

The tabby stayed with us for a long time, and followed us almost out of the public green that lies east of the Eden garden. Whether we had reached the edge of his territory, or he was dissuaded by the dogs that had begun to emerge for their early evening walks, the Eden tabby’s time and space with us came to an end. I hope we find him again, our cat-ambassador to a garden we may never see with our own eyes, but that we might know little more, through him.