“Painting leads to thought and then leaves it behind. The space of painting is a passageway. By trusting the painting as true you become a witness to the effects of events that you didn’t experience directly … a witness to an event in which you didn’t participate, and a proximity to those you have never met.”

Bracha L. Ettinger, 2016

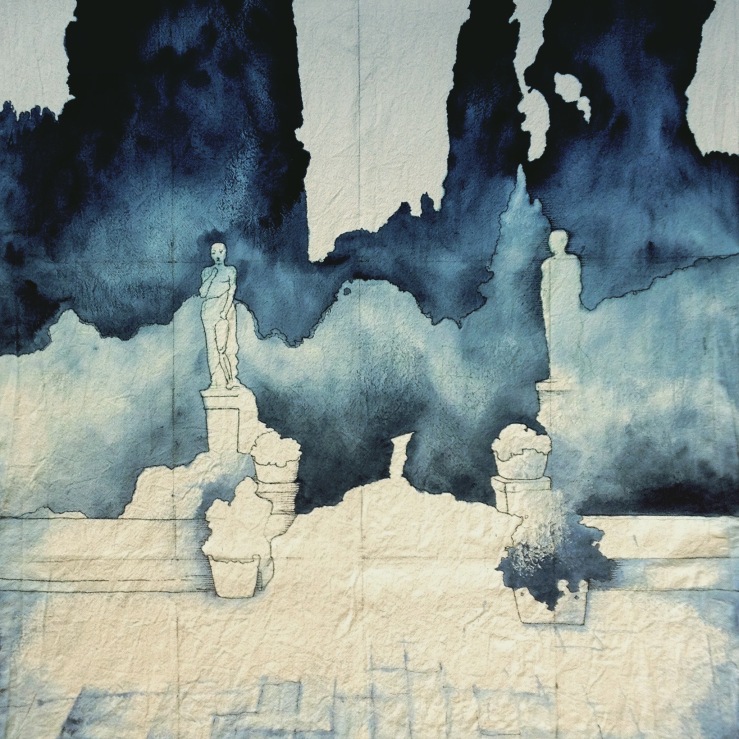

Psychoanalyst and artist Bracha L. Ettinger is here discussing how she understands her own painting practice, which has had a strong focus on the experience of Jewish women in the Holocaust. My own paintings approach a far gentler terrain, even though the Giardino dell’Eden was occupied by the Italian fascist army for a time, and was not always a space of repose and retreat. Yet I find Ettinger’s ideas fruitful for thinking about this work that I am doing in Montreal about a garden that was begun over a century ago, and half a world away.

While she is not the only focus of my project, I often return in my thoughts to Caroline Eden (d. 1928), who I believe to have been the main agent in the conception and creation of this space. This, however, is not the usual perspective. In an article for the Guardian, James Fenton observes that “Caroline was Gertrude Jekyll’s elder sister (but the garden predates Jekyll’s interest in garden design).” Yet the article otherwise attributes every aspect of the garden to Frederick Eden. Similarly, in a review for the Telegraph, Peter Parker remarks on how Frederick “Eden [was] an invalid who was usually to be found on a sun-lounger surrounded by his beloved dachshunds.” But he does not explore the possibility that Caroline Eden was the progenitor of this unusual space. The purpose of both of these articles is to assess the 1903 self-published book, A Garden in Venice, which has only one, named author: Frederick Eden, even if is often written in the first person plural (“we decided”, “our roses”). But the elision between the authorship of this book and the authorship of the design of the garden is something to be questioned, at least because of Frederick Eden’s physical infirmities at the time the garden was made.*

The one author who believes, as I do, that Caroline Eden designed and built the garden on Giudecca has not found archival evidence to prove this thesis. However, in The Garden of Eden – A Secret Garden in Venice, Annemette Fogh makes a compelling choice to be in dialogue with the missing figure of Caroline Eden, encountering her, or her ghost, at the threshold to the garden on the Rio della Croce, and visiting the garden with this ghost as her guide. The book moves in and out of this fiction, and the author gradually develops a relationship with the semi-fictional Caroline Eden around the one thing the two women have in common: love for this garden.

This writing strategy might be criticized as taking liberties with history. Yet I myself know what it is to be so deeply involved in research on a historical subject and site that I dream about the key players at night, forget what year I am living in upon waking, and seem at times to be on the point of dissolving into a profound proximity with the women, historical moments, and spaces that I am straining every resource to discover and understand. When I was working on suffragette spatial histories in Bath, England, I was walking the city by day, looking for their traces, and reading over my notes at night, digging for clues, mapping their trajectories, and looking for patterns. At times I too felt ghosts with me in the room, or on the street, and they were as real as the notebook in my hand. Once I could swear I heard the suffragettes laugh behind me. And one night, an invisible hand pressed gently and warmly into my shoulder as I struggled with a difficult section of my book on women’s role in creation of the built environment of Bath. I think when I open myself so fully to research in this way, that I am receiving on all channels. Am I inventing the laugh, the hand, the ghost? Perhaps. But rather than ignore these moments, I used them as inspiration to write a section of my book as if I had been there at the time. And what I wrote about was a garden – an arboretum that real suffragettes did build on the edges of Bath to commemorate their feminist work to gain all women the vote.

We rest our hands on the round iron bars of the gate that will allow us in, and catch our breath. Sloping up in front of us, spreading like a green bowl, cupping the warm late light that the hollyhocks could not reach, is our wood.

There are more trees than ever; everything has grown. We could not count them all from here. So we go in, pushing against the gate, hearing the satisfying groan of heavy iron, making sure it does not drop against its post for fear of disturbing the peace we have come to find. We fall into silence and begin to walk…

– Architects, Angels, Activists in Bath, 1765-1965, p. 216.

The trees, flowers, heavy iron gate, even the topography of the site were all my findings and based on historical fact. The evening walks that the young women took were also fact. Yet all the framing, and the first-person account, are mine.

While dismissing such writing as fanciful would be the usual response, perhaps texts like mine and Fogh’s could be thought of as writerly outcomes of “fascinance”, the word Ettinger uses to describe “aesthetic openness to the other and the cosmos.” In 1991, art historians Mieke Bal and Norman Bryson critiqued the positivist division between past and present, refuting the idea that either “context” or “authorship” could be genuine, historically-defined certainties. When reaching with sincerity into histories and pasts that we can never truly or fully know, one consequence of this work is that “the art historian is always present in the construction she or he produces.” (p. 243) What also emerges from the effort, however, is more than a subjective description of a historical moment: it is, in fact, a creation. Informed by the pieces of the past that she has been able to find, and the present moment of the researcher, this creation is a thing made of “strings and threads” of intersubjective encounter with the partially known (Ettinger).

So the question of authorship remains, but it is important to keep it, as a question, open, otherwise Caroline Eden fades into the background of the discussion of this garden, as most authors will have her do. Until such time as her own words or drawings can be found, it is important for writers and artists to explore the terrain between what is known and what is unknown about her role in creating this special place in Italy. But even if Caroline Eden does not appear to have written anything about her garden in Venice, her famous sister’s words are resonant when looking at some of the photographs taken of the garden on Giudecca:

… as you move among them every plant seems full of sweet sap or aromatic gum, and as you tread the perfumed carpet the whole air is scented; then of dusky groves of tall Cypress and Myrtle, forming mysterious shadowy woodland temples that unceasingly offer up an incense of their own surprising fragrance … To find oneself standing … in a grove of giant Myrtles fifteen feet high is like having a little chink of the door of heaven opened, as if to show what good things may be beyond!

“The Scents of the Garden,” in Wood and Garden: Notes and Thoughts, Practical and Critical, of a Working Amateur, p. 237) **

In this way, it would seem that gardens, like paintings, can themselves be passages and thresholds to other worlds.

* In 2011, Robin Lane Fox wrote an article for the Financial Times that intimates the influence of the Giudecca garden on Gertrude Jekyll’s still-famous designs and philosophy. While steering clear of attributing the Eden Garden to Caroline Eden, the author does propose a link between the garden in question and Jekyll’s oeuvre, and even if it does not analyse sisterhood as key to that link, the suggestion is there.

** First published in 1899. I am grateful to Robin Lane Fox’s article, cited above, for drawing my attention to this book.

Fin Mars, nous ommes allés uns fois de plus vers Le Jardin d’Eden, ce jour là, il y avait le “gardien” qui a fait une courte apparition et qui n’a rien voulu entendre, malgres nos nombreux coups de sonnette. Je pense que cela est mieux ainsi, car si nous pouvions rentrer(mon mari et moi) il n’y aurait plus aucun mystère et le jardin ne serait donc plus”mysterieux”.J’ai grimpé sur le mur(du côté des habitations) et j’ai vu un jardintrés vert et bien entretenu.Je n’arrive pas à acheter le livre de Annemette Fogh(disparue, helas), car eella a pu rentrer et prendre des photos. Un Monsieur nous a dit qu’il était à vendre pour plusieurs millions.????Bonne journée, et à bientôt Jardin d’Eden réve.

LikeLike